By Evan Robertson, Senior Project Associate

In the world of community, economic, and workforce development, it is easy to be United States-centric. So much of our important work is deeply impacted by our national, state, and local laws and policies. Even within the United States, each region of the country has vastly different, contrasting, milieus of community, economic, and workforce development. Beyond our nation’s boundaries community, economic, and workforce development can look downright alien. From time to time, however, looking past these differences can yield insight into new possibilities and assist in identifying solutions to challenges that local communities are likely to encounter in the future.

We at Market Street have been deeply concerned with the sustainability of the nation’s workforce for a great deal of time - education and talent development remain core components of our processes, we view workforce sustainability as THE issue in our field. Communities who take talent for granted are likely to find themselves at a serious disadvantage in the coming years – recent headquarter relocations such as Expedia’s move from suburban Seattle to its downtown area and the Mercedes-Benz headquarter relocation into the Atlanta area (hint: transit accessibility was a major location factor) are just a few recent talent-driven relocations that highlight businesses’ thirst for locating in areas they perceive as being attractive to tomorrow’s workforce. If talent availability is our key community, economic, and workforce development issue, then the retirement of the baby boom generation is our greatest challenge. Of course, there are many unknowns regarding how communities and businesses will respond to the retirement of the baby boom generation – we simply haven’t experienced such a large swath of our workforce entering retirement age in such a short period of time. Will we fill gaps through promoting immigration? Will robots replace certain types of work? Will businesses selectively downsize? Will GDP be impacted?

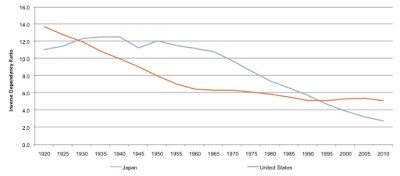

Luckily, for us at least, Japan offers a rare glimpse into the potential challenges and outcomes of severe workforce shortages caused by retirees exiting the labor force. Working age adults typically support retirees by generating tax revenue which, in turn, is used to support social services such as Medicare and social security, or in the case of Japan, its national pension system (Kokumin Nenkin) and the national healthcare system (Kokumin-Kenkō-Hoken). Inverse dependency ratios (i.e. the ratio of residents aged 15 to 64 aged divided by residents aged 65 and over) are a quick and easy way to determine just how many working age adults there are to support a nation’s retiree population. As the following chart displays, Japan’s number of working age adults relative to its retiree population has dropped precipitously since records began in 1920. In 1920, there were roughly 11 residents aged 15 to 64 for every individual aged 65 and over in Japan. By 2010, there were only 2.8 residents aged 15 to 64 for every individual aged 65 and over in the county. By comparison, the United States’ dependency ratio, while in similar decline, has been less severe (the United States’ dependency ratio stood at 5.8 in 2010). These figures are likely to slip further, Japan’s own population projections foresee a continually aging population long in to 2060. As Japan’s workforce continues to enter retirement age, well before the United States’ pending baby boom retirements, it offers communities a clear picture into their future. Thus far, the impact in Japan has been startling.

Inverse Dependency Ratio for Japan and United States, 1920 - 2010

Source: Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Statistics Bureau; U.S. Census Bureau

Source: Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Statistics Bureau; U.S. Census Bureau

A recent Wall Street Journal article describes the profound impact talent shortages are having on Japan’s economy. The country’s gross domestic product declined at an annualized rate of 0.8 percent in the third quarter according to the article, this is particularly interesting since Japan’s unemployment rate stands at 3.4 percent. With the vast majority of the nation’s population employed, one would expect that gross domestic product would be on the rise. Due to the lack of available workers, Japanese companies are cutting back. One company detailed in the article had to close around twenty percent of its approximately 2,000 24-hour restaurants during late night hours. This would be akin to Waffle House locking its doors from say 12 a.m. to 6 a.m. not because there weren’t customers at those hours to sustain the business (trust me, there are), but there was simply no one available to tend to the store during that time. Japanese companies who require more highly skilled talent report intense competition for workers, with highly skilled employees often receiving numerous job offers from other competitors.

As you might suspect, much akin to the United States, Japan’s urban centers typically possess a lower concentration of residents aged 65 and over compared to other areas of the country. As the following map shows, those prefectures in and around Tokyo; Nagoya, and Osaka generally possess a younger population. Much like in the United States, Japan’s urban cores and their ability to develop a built environment attractive to young Japanese residents as well as new immigrants alike will be central to the success or failure of addressing the country’s talent shortages.

If there is one major takeaway, it is this: watch Japan closely over the coming years. They are the first nation to experience a severe workforce shortage caused by a large portion of their population retiring within a short window of time. The policy responses they formulate both at the local and national level may offer ideas to other communities on how to attract and retain top talent in a given community. They could very well earn the distinction of creating new, innovative talent attraction and retention best practices. Of course, some of the policy responses will be out-of-reach to local leaders stateside. A local community’s ability to impact national immigration policy is limited. Other policies, especially those that pertain to welcomeness, inclusion, and place making, will likely provide fertile ground for adoption or tailoring a particular policy to your local community.